By Ryan van Leent & Ian Ryan, SAP

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is underpinning the next technology revolution. This is a revolution that offers huge potential benefits for Social Services. But, despite AI’s promise to accelerate growth and streamline day-to-day operations, AI uptake in the public sector worldwide has been limited. The SAP Institute for Digital Government collaborated with the University of Queensland to examine the challenges and the reasons behind this.

Building a successful AI transformation programme

We studied nine AI projects and interviewed and surveyed data scientists, system developers, domain experts, and managers. Through our inquiry we identified a set of common challenges that slow down AI adoption. Our research suggests that to ensure successful use of AI, public sector organizations need to initiate transformation programmes that systematically address these challenges and maximise value creation for a range of stakeholders, especially citizens.

Guidelines for government leaders

We present the following guidelines for delivering successful AI programmes in Social Services:

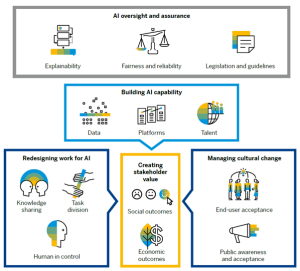

1. Building AI capability: AI development is resource-intensive and requires significant ongoing commitment to secure high-quality data, platforms, and talent.

2. Redesigning Work for AI: AI systems’ growing ability to outperform humans in some tasks can represent a compelling managerial challenge. Despite its capabilities, AI is limited in its ability to understand context and interpret situations. Thus, it is important to keep people in the loop as safeguards to machine fallacies.

3. AI oversight and assurance: AI decision-making can be opaque for human decision-makers and some AI has been shown to be biased and discriminatory. Public sector organizations need to establish precise oversight and assurance mechanisms to minimize risks for stakeholders (especially vulnerable people).

4. Managing cultural change: Public sector organizations can face resistance both from their internal and external consumers regarding use of AI for decision-making.

5. Creating stakeholder value: Justifying public expenditure for projects that are risky and have unclear value metrics, can make it difficult to be an early adopter of AI.

Figure 1: A framework for building a successful AI transformation programme

Further research

This first stage of our research identified common AI challenges for government and developed a high-level framework of capabilities, capacities and processes that are needed to create value from AI while minimizing the risks. Further research (to be published in future editions of the ESN newsletter) will explore the specific challenges of AI “explainability’ and building AI capability.

The research paper can be downloaded here